Growing Up In Depression-Era Ripley County

My parents have been married 35 years, and like most couples who have been well - married for so long, they appear to have many common tastes and personality traits. But it was not always thus.

As a child, I felt them to be so different, one from the other, that it seemed strange they should have ever married. Physically, my mother was tiny, neat and presented a deceptively delicate appearance; while daddy was so big, so robust, with the strength of Hercules and to a little child, a bulwark against the world, fearless and steadfast and ever at hand when needed.

However, as I reached the age where a child sheds its cocoon of “parent-worship” and begins to see the world with a critical and sometimes cold eye, it became all too apparent that looks could deceive and my mother and daddy were not exactly what they had seemed to me.

I soon understood that my little mother was indeed the strong, dependable partner and daddy was the playmate, who provided the fun and the excitement.

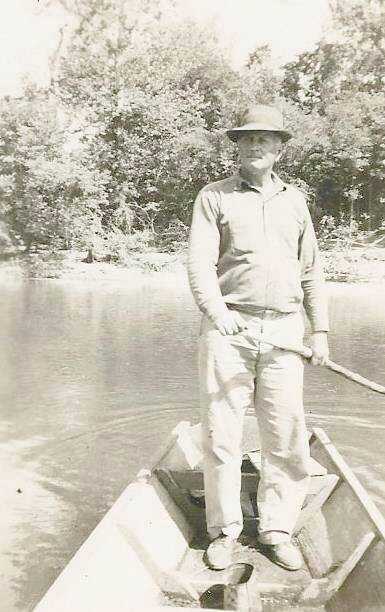

It was he who taught we children to swim and to fish, to gather the wild flowers, fruits and nuts. He was always at hand for a ball game or a trek through the woods and by the river. It was he who thought up, and joined in, the delightful game of removing our footwear to see who could run the farthest in the soft, clinging snow. This was great fun and we thought the one who won was so tough and courageous.

He would go wading with us in a drying creek bed to muddy the water and make the fish come to the surface, where they could be caught by hand. This requires a bit of skill, to grab a catfish from the water and not get pricked by his “whiskers.” I remember once daddy got a snakebite on his toe while doing this stunt. At that time we didn’t know why he made us promise to give up this particular sport. It was so much fun, and of course he didn’t tell us what had happened then, probably he did not wish us to become fearful.

Daddy could box and wrestle. He could walk fast on high stilts he made for us; he could do a higher pole vault or running jump than anyone; he could toss a dime into the air and hit it, shooting from hip or shoulder, as it came down; he could always catch the biggest fish and could swim across the river under water. There just wasn’t anything that he could do --- for fun.

Only thing, he just never seemed quite able to provide the necessities of everyday living for his family. He was hampered somewhat by certain physical disabilities that, while they were not then apparent, had already begun to bother him while still quite young.

Too, he was much too generous and not at all thrifty, like mama. When he had money, he could be counted on to provide toys, candy and other goodies to put the shine in the eyes of a child; but all too often he was broke and in debt and then where were the raincoats, the overshoes, the bread and milk to come from, if mama didn’t go “out” to work for more fortunate neighbors? Daddy was always dreaming impossible dreams and talking of improbable schemes to make us rich, but we learned early that none of these things would ever come true.

Mama’s dreams, tho less lofty, were somehow made to come true. She was buzzing like a little humming bird all the time; cooking a tasty meal out of practically nothing (this is not just a figure of speech); making over old clothes; washing on an old rub board and all the countless other chores women in her position did at that time. In addition to the homemaking, she was working “out” whenever she could, to accumulate a few dimes and dollars to furnish her four children with a better education than she had, so they might escape the hard life she had been born, and later married, into.

Needless to say, at the time, I failed to appreciate my mother’s selfless devotion to her family and it seemed to me that she was stern, lacking in gaiety and entirely devoted to that hateful “duty.” How well I remember one incident from my childhood, tho, when she allowed her love and understanding of the needs of a child to overcome for a moment her thrifty and serious nature.

Picture, if you will, a hot, dusty day, an old white school house, badly in need of paint; and milling noisily about the hard, bare schoolyard, a throng of eager, excited youngsters. See how they dart about, chasing each other, flailing arms and legs, jumping and shouting for the sheer joy of being alive. Yet, for all the running and jumping, they are careful, for they are all dressed in unaccustomed splendor. New overalls and old overalls with new patches; scrimpy little cotton dresses hastily run up by a mother’s overworked hands. They certainly mustn’t get soiled or torn, for, look, they’re going to the circus. The great day has finally arrived and for only 35 cents each, teacher is taking everyone in a truck (this before the day of the shiny, orange school buses that now transport the youngsters so gaily and efficiently) all the way to the town, 15 whole miles. Everyone is to see everything in the circus and eat peanuts or popcorn and cotton candy, besides. What an adventure. What a day. What a wonderful world.

But -- here’s a note of gloom in this gay scene. Here’s someone outside the hilarious throng. See the skinny little girl with the straight hair and scraggly bangs? There she stands at the edge of the school yard, huddled down into her faded little blue dress, her eyes strained and her thin little body tense with worry and disappointment.

“Ruthie, yuh think she’ll come? Yuh think yuh mom’ll bring the money? Aw, I bet you don’t get to go.” A sympathetic but doubtful playmate pauses for a moment with intent to comfort the forlorn one, then dashes away, too taken up with her own delight to really care.

But the little lonely one warrants yet more attention. A couple of naughty little boys stop their mock battle for a moment to tease. “Ho, Ruthie can’t go to the circus. We’re gonna see the elephants an everything. Maybe even tigers. Yuh ole lady too stingy to fork over the dough for the tickets. Y’all just too poor for anything.” One boy tosses a pebble at her feet and it hits just where the too-old, too-small shoe has cracked and broke. But she doesn’t even feel the sting. Her mind is absorbed by a pain more intense than any physical hurt could ever be.

That miserable little creature was, of course, myself, age nine. I shall never forget that moment, that forever-moment, suspended in that hot, dusty school yard, with the sun beating down on my little tow-head and my heart breaking, while I waited for my mother to bring me the money she had half-way promised, if the check for the calf came and if it amounted to enough so she felt we could spare a few cents for fun.

I just knew she wouldn’t come. She would never let me have that 35 cents. It was a fortune in that second year of the depression and there were three other children to feed, clothe and educate. I was too young, tho, to understand my mother’s problems and felt she could surely let me have that old 35 cents to go to the circus. All the others were going and I, who usually felt so left out, just had to, this once, be like the others and have fun like they did. But I just knew it would never happen. Already I had given up in despair and was ready to trudge home, my unshed tears an unbearable burden.

Then, can it be true, or am I dreaming? Is that little figure hurrying, yes, running, through the sparse woods lot, my own mama? Yes, it is. She’s coming and my life has been saved. Suddenly my friends dash to my side to tell me I, too, will be going to the circus, to see and feel and taste and smell, to really live, to be one of them.

There have been many good moments, moments to remember, since then; but none that I remember so well as that moment when my mother, breathless and hot from hurrying, put that quarter and those two nickels in my eager little hand. The circus? Perhaps it was all I had dreamed of. No doubt there were elephants, tigers, peanuts and everything else I have enjoyed at later circuses; but that I don’t really remember. I do, tho, remember the tight little smile on mama’s face, the light in her eyes, even the exact location of the patch on her old, old dress. And to think she could have a new dress for that 35 cents, or she could have bought seven dozen eggs for that 35 cents. Instead, she chose to give it to me for something which was so very important to me.

Daddy, of course, gave us many happy, exciting hours to remember, hours of fun and adventure. But that was not all. There is one night I remember when he came through in a crisis like no-one has ever done for me, before or since. Perhaps he doesn’t even remember that cold, wet, dreary night but I do.

This was during my second year of high school; and the family still desperately poor, I was staying with a dear old lady in town, giving her company and a nominal fee for a room, so I could continue with that all-important education. This was a time of struggle and much hardship for me, but a time of achievement, too. I was always either ecstatically happy or in utter despair. In other words, I was young, ambitious and so alive it hurts to think of it.

After long hours of study and much practice, I had arrived at the important position of captain of the school debating team. I was really good. And why not, for did I not plan on becoming a famous lady lawyer, devoting my silver-tongued eloquence and keen mind to the cause of justice and to the aid of the downtrodden and forsaken?

For the moment, the only goal I had was to attend the state debating contest to be held in a city some 100 miles from home on the next day. I not only had nothing to wear, but was flat broke. How would I possibly bring myself to tell my favorite teacher, the debating coach, these disgraceful facts. With the terrifying pride of the young, I found it impossible to speak of my family’s poverty to anyone. It never occurred to me that there were many others in a like position and that it was nothing to cause one shame.

My mother certainly had some idea of my plight and would have sent me money is if she possibly could, but I had heard nothing from her, so had just given up. The only thing left for me to do was either to commit suicide or be taken desperately ill. Since mother and daddy could not afford a funeral, I decided on the latter course. However, I was in a cold sweat for fear I could not put it over. My mind was paralysed and so was my body. All I could do was sit in my room, too miserable even to cry. No doubt if this had continued through the night, it would have required little acting ability to feign illness.

Suddenly my door opened and my landlady said softly “young lady, there’s someone at the front door to see you -- your daddy. He won’t even come in, he’s so dripping wet and muddy, so you’d better come alive and come out to talk to him - and hurry. He’ll catch his death standing out in the cold, wet as he is.”

Oh, my father, there he stood, indeed dripping and shivering but grinning nevertheless, smiling the carefree, conquering smile. And who would have a better right? It must have required a heroic effort for him to leave the comfort of his fireside and walk (naturally he didn’t have a car) the 15 miles to town in the cold slashing rain. He was carrying a $10 bill, somehow acquired at the last moment especially for me, and a box containing a dress for me to wear on the great occasion, the box wrapped at least part of the trip by his old raincoat.

Being young and completely self-engrossed, I doubt that I even thanked him properly. I was much too interested in the $10 bill and the dress, which turned out to be rather hideous fascia creation, cast off by some fortunate woman of our acquaintance with more money than taste. To me, tho, it was beautiful, just perfect. I remember every detail, even to the fact that it was trimmed with black, which was so grown-up and was too tight in the rear, which pleased me much.

My landlady, a lady of 84 and possessing more sense than myself, insisted that daddy stay the night in the comfort of her warm little house. He declined, telling us he would stay downtown in the hotel. Surely, I might have realized this was a noble lie, that he had no money for a room in a hotel; and would proceed to trudge the lonely miles home, wet, cold and tired, as he had come.

However, I let him go with hardly a thought, and rushed to my room to try on the dress and to posture and declaim before my mirror, planning my brilliant success of the morrow.

If you are interested, I was a dismal flop; something to my timing and threw the entire debating team off. I try to remember the humiliation I must have suffered by this defeat, but find it impossible.

I do, though, remember the $10 bill, the fascia dress and that wonderfully strong, dependable man, my daddy, who could do anything.